- Lesson 1 - Introduction

- Lesson 2 - JavaScript Where To

- Lesson 3 - JavaScript Output

- Lesson 4 - JavaScript Syntax

- Lesson 5 - JavaScript Statement

- Lesson 6 - JavaScript Comments

- Lesson 7 - JavaScript Variables

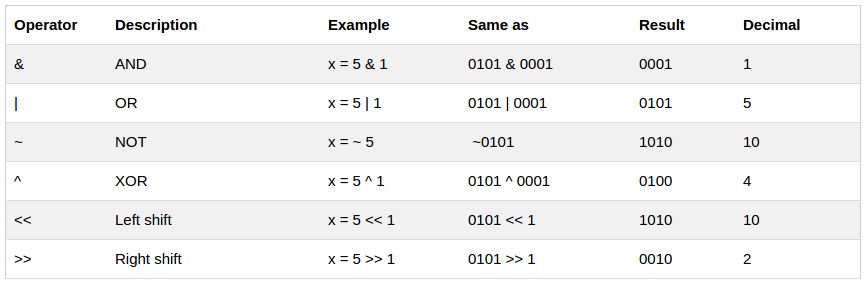

- Lesson 8 - JavaScript Operators

- ...

- Lesson 17 - JS String Methods

- Lesson 18 - JS Numbers

- Lesson 19 - JS Number Methods

- Lesson 20 - JS Math Object

- Lesson 21 - JavaScript Dates

- Lesson 22 - JS Arrays

- Lesson 23 - JS Booleans

- Lesson 24 - JS Comparison and Logical Operators

- Lesson 25 - JS Condition If Else Statements

- Lesson 26 - JS JavaScript Switch Statement

- Lesson 27 - JS For Loop

- Lesson 28 - JS While

- Lesson 29 - JS Break and Continue

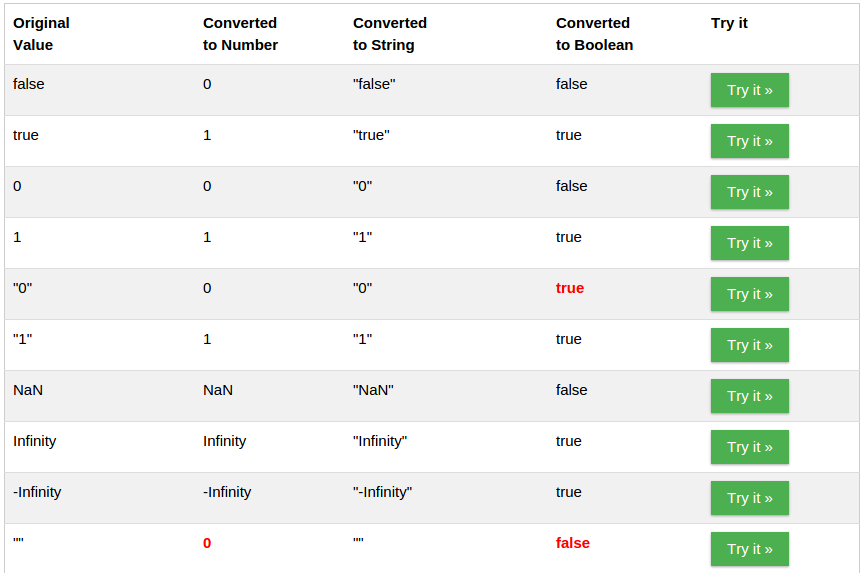

- Lesson 30 - JS Type Conversion

- Lesson 31 - JS Regular Expression

- Lesson 32 - JS Throw and Try to Catch

- Lesson 33 - JS Debugging

- Lesson 34 - JS Hoisting

- Lesson 35 - JS Use Strict

- Lesson 36 - JS Style Guide and Coding Conventions

- Lesson 37 - JS Best Practices

- Lesson 38 - JS Common Mistakes

- Lesson 39 - JS Performance

- Lesson 40 - JS JSON

This page contains some examples of what JavaScript can do.

One of many JavaScript HTML methods is getElementById().

This example uses the method to "find" an HTML element (with id="demo") and changes the element content (innerHTML) to "Hello JavaScript":

Example

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Hello JavaScript";

<button type="button" onclick="document.getElementById('tanggal').innerHTML = Date()">

Click me to find out the date is

</button>

<p id="tanggal"></p>

This example changes an HTML image by changing the src (source) attribute of an tag:

Prinsipnya adalah

onclick="getElementById('myImage').src='myNewImage';"

Sample

<img id="myImage" src="http://res.cloudinary.com/medio/image/upload/v1467519618/pic_bulboff_diye3u.gif" alt=""><br>

<button type="button" onclick="document.getElementById('myImage').src='http://res.cloudinary.com/medio/image/upload/v1467519606/pic_bulbon_hnaava.gif' ">

Click to ON Lamp

</button>

<button type="button" onclick="document.getElementById('myImage').src='http://res.cloudinary.com/medio/image/upload/v1467519618/pic_bulboff_diye3u.gif' ">Turn OFF again</button>

Changing the style of an HTML element, is a variant of changing an HTML attribute:

Prinsip:

document.getElementById("demo").style.fontSize = "25px";

Sample:

<h2>We going to change Font Size text & Color</h2>

<p id="textme">This is the text we going to change the font style</p>

<button type="button" onclick="document.getElementById('textme').style.fontSize='25px'">Change Size</button>

<button type="button" onclick="document.getElementById('textme').style.color='red'">Change Color</button>

Hiding HTML elements can be done by changing the display style:

Prinsip:

document.getElementById("demo").style.display="none";

Sample:

<h1 id="judul">Saya ingin menyembunyikan ini sesaat saya menekan tombol</h1>

<button type="button" onclick="document.getElementById('judul').style.display='none'">

Tombol

</button>

Showing hidden HTML elements can also be done by changing the display style:

Prinsip:

document.getElementById("demo").style.display="block";

Sample:

<h3>Menampilkan text yang tersembunyi</h3>

<p id="sembunyi" style="display:none;">Hello World Dyo!!!</p>

Klik button untuk menampilkan sesuatu

<button type="button" onclick="document.getElementById('sembunyi').style.display='block'">

Click me

</button>

It is difficult to answer the question "What can JavaScript do?"

The examples on this page is only a few examples of the possibilities JavaScript provides.

JavaScript can be placed in the <body> and the <head> sections of an HTML page.

In HTML, JavaScript code must be inserted between <script> and </script> tags.

Example

<script>

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "My First JavaScript";

</script>

Note:

Older examples may use a type attribute: <script type="text/javascript">.

This type attribute is not required. JavaScript is the default scripting language in HTML.

A JavaScript function is a block of JavaScript code, that can be executed when "asked" for. For example, a function can be executed when an event occurs, like when the user clicks a button.

sample:

<h3 id="rubah">Merubah text ini menjadi text lain</h3>

<script>

function myFunction() {

document.getElementById('rubah').innerHTML="Text telah berubah menjadi yang ini."

}

</script>

<p>

<button type="button" onclick="myFunction()">Click deh</button>

</p>

myScript.js

function myFunction() {

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Paragraph changed.";

}

put the extention link:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<script src="myScript.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Sample:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<h1>External JavaScript</h1>

<p id="demo">A Paragraph.</p>

<button type="button" onclick="myFunction()">Try it</button>

<p><strong>Note:</strong> myFunction is stored in an external file called "myScript.js".</p>

<script src="myScript.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

JavaScript can "display" data in different ways:

Writing into an alert box, using window.alert(). Writing into the HTML output using document.write(). Writing into an HTML element, using innerHTML. Writing into the browser console, using console.log().

You can use an alert box to display data:

<script>

window.alert(5 + 6)

</script>

For testing purposes, it is convenient to use document.write():

<script>

document.write(8 + 6);

</script>

Other sample:

<button type="button" onclick="document.write(5 + 7)">

Try it!

</button>

To access an HTML element, JavaScript can use the document.getElementById(id) method. Untuk mengakses sebuah elemen HTML, JavaScript dapat menggunakan metode document.getElementById (id).

The id attribute defines the HTML element. The innerHTML property defines the HTML content: Atribut id mendefinisikan elemen HTML. Properti innerHTML mendefinisikan konten HTML:

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = 5 + 8;

</script>

In your browser, you can use the console.log() method to display data.

Activate the browser console with F12, and select "Console" in the menu.

<script>

console.log(5 +7)

</script>

JavaScript syntax is the set of rules, how JavaScript programs are constructed. sintaks JavaScript adalah seperangkat aturan, bagaimana JavaScript program dibangun.

A computer program is a list of "instructions" to be "executed" by the computer.

In a programming language, these program instructions are called statements.

JavaScript is a programming language.

JavaScript statements are separated by semicolons.

var x = 5;

var y = 8;

var z = x + y;

document.getElementById("contoh1").innerHTML = z;

JavaScript statements are composed of:

Values, Operators, Expressions, Keywords, and Comments.

The JavaScript syntax defines two types of values: Fixed values and variable values.

Fixed values are called literals. Variable values are called variables.

The most important rules for writing fixed values are:

Numbers are written with or without decimals:

10.5

1001

Strings are text, written within double or single quotes:

"John Doe"

'John Doe'

In a programming language, variables are used to store data values.

JavaScript uses the var keyword to declare variables.

An equal sign is used to assign values to variables.

In this example, x is defined as a variable. Then, x is assigned (given) the value 6:

var x;

x = 6;

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = x;

JavaScript uses an assignment operator ( = ) to assign values to variables:

var x = 7;

var y = 8;

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = x + y;

Other sample:

(5 + 6) * 10

An expression is a combination of values, variables, and operators, which computes to a value.

The computation is called an evaluation.

For example, 5 * 10 evaluates to 50:

5 * 10

Expressions can also contain variable values:

x * 10

The values can be of various types, such as numbers and strings.

For example, "John" + " " + "Doe", evaluates to "John Doe":

"John" + " " + "Doe"

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "John" + " " + "Doe";

JavaScript keywords are used to identify actions to be performed.

The var keyword tells the browser to create a new variable:

var x = 5 + 6;

var y = x * 10;

Not all JavaScript statements are "executed".

Code after double slashes // or between /* and */ is treated as a comment.

Comments are ignored, and will not be executed:

var x = 5; // I will be executed

// var x = 6; I will NOT be executed

Identifiers are names.

In JavaScript, identifiers are used to name variables (and keywords, and functions, and labels).

The rules for legal names are much the same in most programming languages.

In JavaScript, the first character must be a letter, an underscore (_), or a dollar sign ($).

Subsequent characters may be letters, digits, underscores, or dollar signs.

Numbers are not allowed as the first character. This way JavaScript can easily distinguish identifiers from numbers.

The variables lastName and lastname, are two different variables.

lastName = "Doe";

lastname = "Peterson";

JavaScript does not interpret VAR or Var as the keyword var.

Historically, programmers have used three ways of joining multiple words into one variable name:

Hyphens:

first-name, last-name, master-card, inter-city.

Underscore:

first_name, last_name, master_card, inter_city.

Camel Case:

FirstName, LastName, MasterCard, InterCity.

In programming languages, especially in JavaScript, camel case often starts with a lowercase letter:

firstName, lastName, masterCard, interCity.

Hyphens are not allowed in JavaScript. It is reserved for subtractions.

JavaScript uses the Unicode character set.

Unicode covers (almost) all the characters, punctuations, and symbols in the world.

For a closer look, please study our Complete Unicode Reference.

In HTML, JavaScript statements are "instructions" to be "executed" by the web browser.

This statement tells the browser to write "Hello Dolly." inside an HTML element with id="demo":

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Hello Dolly.";

Most JavaScript programs contain many JavaScript statements.

The statements are executed, one by one, in the same order as they are written.

In this example x, y, and z are given values, and finally z is displayed:

Example

var x = 5;

var y = 6;

var z = x + y;

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = z;

JavaScript programs (and JavaScript statements) are often called JavaScript code.

Semicolons separate JavaScript statements.

Add a semicolon at the end of each executable statement:

a = 5;

b = 6;

c = a + b;

document.write(c);

When separated by semicolons, multiple statements on one line are allowed:

x = 7; y = 6; z = x + y;

document.write(z);

On the web, you might see examples without semicolons. Ending statements with semicolon is not required, but highly recommended.

JavaScript ignores multiple spaces. You can add white space to your script to make it more readable.

The following lines are equivalent:

var person = "Hege";

var person="Hege";

A good practice is to put spaces around operators ( = + - * / ):

var x = y + z;

For best readability, programmers often like to avoid code lines longer than 80 characters.

If a JavaScript statement does not fit on one line, the best place to break it, is after an operator:

Example

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML =

"Hello Dolly.";

JavaScript statements can be grouped together in code blocks, inside curly brackets {...}.

The purpose of code blocks is to define statements to be executed together.

One place you will find statements grouped together in blocks, are in JavaScript functions:

Example

function myFunction() {

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Hello Dolly.";

document.getElementById("myDIV").innerHTML = "How are you?";

}

JavaScript statements often start with a keyword to identify the JavaScript action to be performed.

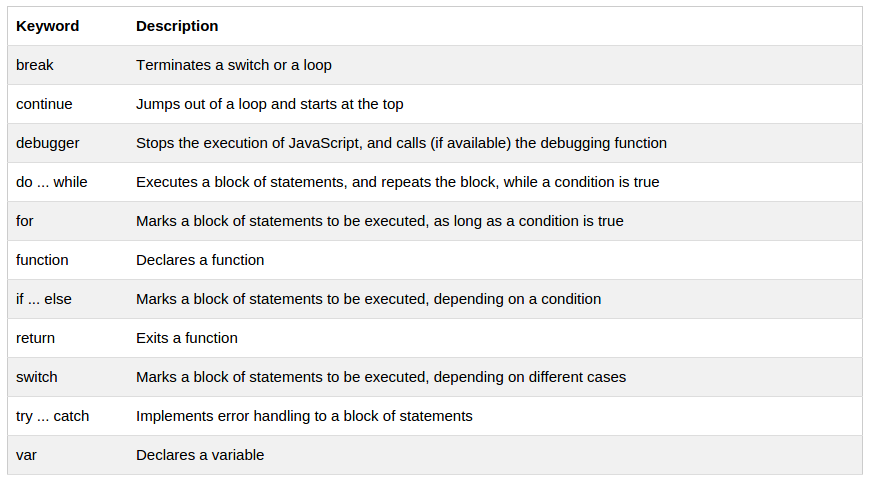

Here is a list of some of the keywords you will learn about in this tutorial:

JavaScript comments can be used to explain JavaScript code, and to make it more readable.

JavaScript comments can also be used to prevent execution, when testing alternative code.

Single line comments start with //.

Any text between // and the end of the line will be ignored by JavaScript (will not be executed).

This example uses a single-line comment before each code line:

Example

// Change heading:

document.getElementById("myH").innerHTML = "My First Page";

// Change paragraph:

document.getElementById("myP").innerHTML = "My first paragraph.";

This example uses a single line comment at the end of each line to explain the code:

Example

var x = 5; // Declare x, give it the value of 5

var y = x + 2; // Declare y, give it the value of x + 2

Multi-line comments start with /* and end with */.

Any text between /* and */ will be ignored by JavaScript.

This example uses a multi-line comment (a comment block) to explain the code:

Example

/*

The code below will change

the heading with id = "myH"

and the paragraph with id = "myP"

in my web page:

*/

document.getElementById("myH").innerHTML = "My First Page";

document.getElementById("myP").innerHTML = "My first paragraph.";

It is most common to use single line comments. Block comments are often used for formal documentation.

Using comments to prevent execution of code is suitable for code testing.

Adding // in front of a code line changes the code lines from an executable line to a comment.

This example uses // to prevent execution of one of the code lines:

Example

//document.getElementById("myH").innerHTML = "My First Page";

document.getElementById("myP").innerHTML = "My first paragraph.";

This example uses a comment block to prevent execution of multiple lines:

Example

/*

document.getElementById("myH").innerHTML = "My First Page";

document.getElementById("myP").innerHTML = "My first paragraph.";

*/

JavaScript variables are containers for storing data values.

In this example, x, y, and z, are variables:

Example

var x = 5;

var y = 6;

var z = x + y;

From the example above, you can expect:

x stores the value 5

y stores the value 6

z stores the value 11

In this example, price1, price2, and total, are variables:

Example var price1 = 5; var price2 = 6; var total = price1 + price2;

Example

var price1 = 5;

var price2 = 6;

var total = price1 + price2;

Example:

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var price1 = 5;

var price2 = 6;

var total = price1 + price2;

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML =

"The total is: " + total;

</script>

In programming, just like in algebra, we use variables (like price1) to hold values.

In programming, just like in algebra, we use variables in expressions (total = price1 + price2).

From the example above, you can calculate the total to be 11.

JavaScript variables are containers for storing data values.

All JavaScript variables must be identified with unique names.

These unique names are called identifiers.

Identifiers can be short names (like x and y), or more descriptive names (age, sum, totalVolume).

The general rules for constructing names for variables (unique identifiers) are:

- Names can contain letters, digits, underscores, and dollar signs.

- Names must begin with a letter

- Names can also begin with $ and _ (but we will not use it in this tutorial)

- Names are case sensitive (y and Y are different variables)

- Reserved words (like JavaScript keywords) cannot be used as names.

JavaScript identifiers are case-sensitive.

In JavaScript, the equal sign (=) is an "assignment" operator, not an "equal to" operator.

This is different from algebra. The following does not make sense in algebra:

x = x + 5

In JavaScript, however, it makes perfect sense: it assigns the value of x + 5 to x.

(It calculates the value of x + 5 and puts the result into x. The value of x is incremented by 5.)

The "equal to" operator is written like == in JavaScript.

JavaScript variables can hold numbers like 100, and text values like "John Doe".

In programming, text values are called text strings.

JavaScript can handle many types of data, but for now, just think of numbers and strings.

Strings are written inside double or single quotes. Numbers are written without quotes.

If you put quotes around a number, it will be treated as a text string.

Example

var pi = 3.14;

var person = "John Doe";

var answer = 'Yes I am!';

Creating a variable in JavaScript is called "declaring" a variable.

You declare a JavaScript variable with the var keyword:

var carName;

After the declaration, the variable has no value. (Technically it has the value of undefined)

To assign a value to the variable, use the equal sign:

carName = "Volvo";

You can also assign a value to the variable when you declare it:

var carName = "Volvo";

It's a good programming practice to declare all variables at the beginning of a script.

Example:

<p id="sample"></p>

<script>

var schoolName = "Universitas Indonesia";

document.getElementById("sample").innerHTML = schoolName;

</script>

You can declare many variables in one statement.

Start the statement with var and separate the variables by comma:

var person = "John Doe", carName = "Volvo", price = 200;

A declaration can span multiple lines:

var person = "John Doe",

carName = "Volvo",

price = 200;

In computer programs, variables are often declared without a value. The value can be something that has to be calculated, or something that will be provided later, like user input.

A variable declared without a value will have the value undefined.

The variable carName will have the value undefined after the execution of this statement:

Example

var carName;

If you re-declare a JavaScript variable, it will not lose its value.

The variable carName will still have the value "Volvo" after the execution of these statements:

Example

var carName = "Volvo";

var carName;

As with algebra, you can do arithmetic with JavaScript variables, using operators like = and +:

Example

var x = 5 + 2 + 3;

document.write(x);

document.write(x)

or

var y = "John" + " " + "Doe";

document.write(y)

or

var z = "5" + 2 + 3;

document.write(z)

If you add a number to a string, the number will be treated as string, and concatenated.

Example

Assign values to variables and add them together:

var x = 5; // assign the value 5 to x

var y = 2; // assign the value 2 to y

var z = x + y; // assign the value 7 to z (x + y)

Example

Assign values to variables and add them together:

var x = 5; // assign the value 5 to x

var y = 2; // assign the value 2 to y

var z = x + y; // assign the value 7 to z (x + y)

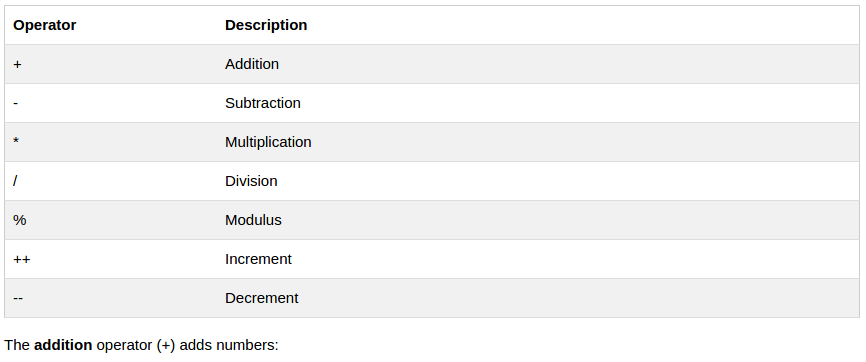

Arithmetic operators are used to perform arithmetic on numbers (literals or variables).

The addition operator (+) adds numbers:

var x = 5;

var y = 2;

var z = x + y;

The multiplication operator (*) multiplies numbers.

var x = 5;

var y = 2;

var z = x * y;

Assignment operators assign values to JavaScript variables.

The assignment operator (=) assigns a value to a variable.

var x = 10;

The addition assignment operator (+=) adds a value to a variable.

Assignment

var x = 10;

x += 5;

The + operator can also be used to add (concatenate) strings.

When used on strings, the + operator is called the concatenation operator.

Example

txt1 = "John";

txt2 = "Doe";

txt3 = txt1 + " " + txt2;

The result of txt3 will be:

John Doe

The += assignment operator can also be used to add (concatenate) strings:

Example

txt1 = "What a very ";

txt1 += "nice day";

The result of txt1 will be:

What a very nice day

Adding two numbers, will return the sum, but adding a number and a string will return a string:

Example

x = 5 + 5;

y = "5" + 5;

z = "Hello" + 5;

The result of x, y, and z will be:

10

55

Hello5

The rule is: If you add a number and a string, the result will be a string!

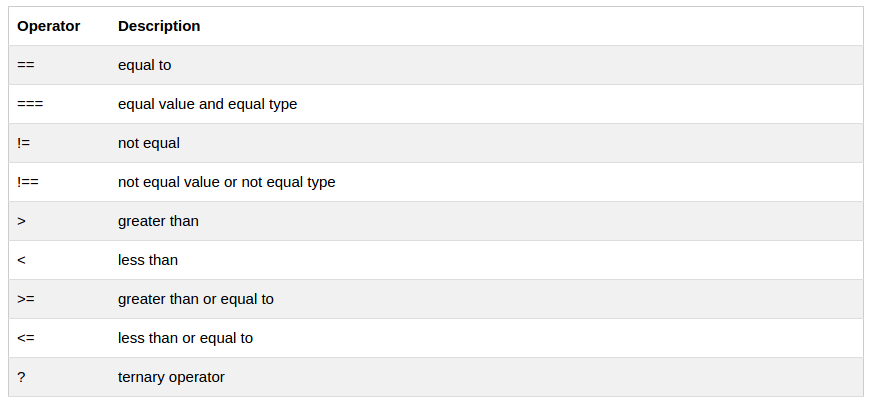

Comparison and logical operators are described in the JS Comparisons chapter.

Operator Description

typeof Returns the type of a variable

instanceof Returns true if an object is an instance of an object type

Type operators are described in the JS Type Conversion chapter.

String, Number, Boolean, Array, Object.

JavaScript variables can hold many data types: numbers, strings, arrays, objects and more:

var length = 16; // Number

var lastName = "Johnson"; // String

var cars = ["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"]; // Array

var x = {firstName:"John", lastName:"Doe"}; // Object

In programming, data types is an important concept.

To be able to operate on variables, it is important to know something about the type.

Without data types, a computer cannot safely solve this:

var x = 16 + "Volvo";

Does it make any sense to add "Volvo" to sixteen? Will it produce an error or will it produce a result?

JavaScript will treat the example above as:

var x = "16" + "Volvo";

When adding a number and a string, JavaScript will treat the number as a string.

var x = 16 + "Volvo";

var x = "Volvo" + 16;

JavaScript evaluates expressions from left to right. Different sequences can produce different results:

Example:

var x = 16 + 4 + "Volvo";

Result:

20Volvo

Example:

var x = "Volvo" + 16 + 4;

Result:

Volvo164

In the first example, JavaScript treats 16 and 4 as numbers, until it reaches "Volvo".

In the second example, since the first operand is a string, all operands are treated as strings.

Booleans can only have two values: true or false.

Example

var x = true;

var y = false;

Booleans are often used in conditional testing.

JavaScript arrays are written with square brackets.

Array items are separated by commas.

The following code declares (creates) an array called cars, containing three items (car names):

Example

var cars = ["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"];

Array indexes are zero-based, which means the first item is [0], second is [1], and so on.

You will learn more about arrays later in this tutorial.

JavaScript objects are written with curly braces.

Object properties are written as name:value pairs, separated by commas.

Example

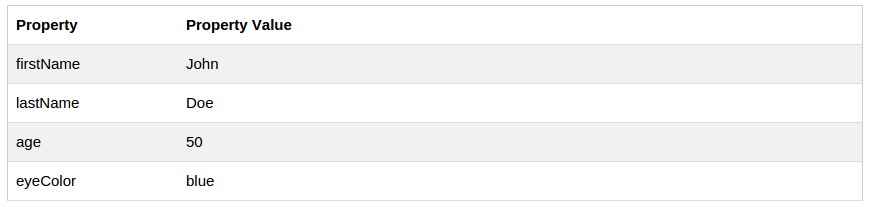

var person = {firstName:"John", lastName:"Doe", age:50, eyeColor:"blue"};

The object (person) in the example above has 4 properties: firstName, lastName, age, and eyeColor.

You will learn more about objects later in this tutorial.

You can use the JavaScript typeof operator to find the type of a JavaScript variable:

Example

typeof "John" // Returns string

typeof 3.14 // Returns number

typeof false // Returns boolean

typeof [1,2,3,4] // Returns object

typeof {name:'John', age:34} // Returns object

In JavaScript, an array is a special type of object. Therefore typeof [1,2,3,4] returns object.

In JavaScript, a variable without a value, has the value undefined. The typeof is also undefined.

Example

var person; // Value is undefined, type is undefined

Any variable can be emptied, by setting the value to undefined. The type will also be undefined.

Example

person = undefined; // Value is undefined, type is undefined

An empty value has nothing to do with undefined.

An empty string variable has both a value and a type.

Example

var car = ""; // The value is "", the typeof is string

In JavaScript null is "nothing". It is supposed to be something that doesn't exist.

Unfortunately, in JavaScript, the data type of null is an object.

Note You can consider it a bug in JavaScript that typeof null is an object. It should be null. You can empty an object by setting it to null:

Example

var person = null; // Value is null, but type is still an object

You can also empty an object by setting it to undefined:

Example

var person = undefined; // Value is undefined, type is undefined

Difference Between Undefined and Null

typeof undefined // undefined

typeof null // object

null === undefined // false

null == undefined // true

A JavaScript function is a block of code designed to perform a particular task.

A JavaScript function is executed when "something" invokes it (calls it).

function myFunction(p1, p2) {

return p1 * p2; // The function returns the product of p1 and p2

}

Example

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

function myFunction(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

// memanggil function dengan getElement dari luar block function iu sendiri.

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = myFunction(5, 3);

</script>

A JavaScript function is defined with the function keyword, followed by a name, followed by parentheses ().

Function names can contain letters, digits, underscores, and dollar signs (same rules as variables).

The parentheses may include parameter names separated by commas: (parameter1, parameter2, ...)

The code to be executed, by the function, is placed inside curly brackets: {}

function name(parameter1, parameter2, parameter3) {

code to be executed

}

-

Function parameters are the names listed in the function definition.

-

Function arguments are the real values received by the function when it is invoked.

-

Inside the function, the arguments behave as local variables.

The code inside the function will execute when "something" invokes (calls) the function:

- When an event occurs (when a user clicks a button)

- When it is invoked (called) from JavaScript code

- Automatically (self invoked)

- You will learn a lot more about function invocation later in this tutorial.

When JavaScript reaches a return statement, the function will stop executing. Saat JS mendapat return statement, function akan berhenti eksekusi

If the function was invoked from a statement, JavaScript will "return" to execute the code after the invoking statement. Jika function sudah dipanggil dari statement, JS akan 'mengembalikan' nya untuk mengeksekusi kode tersebut setelah di statement panggil.

Functions often compute a return value. The return value is "returned" back to the "caller": Function sering menjalankan nilai pengembalian. Nilai pengembalian di kembalikan kepada sipemanggil

Example

Calculate the product of two numbers, and return the result:

var x = myFunction(4, 3); // Function is called, return value will end up in x

function myFunction(a, b) {

return a * b; // Function returns the product of a and b

}

The result in x will be:

12

You can reuse code: Define the code once, and use it many times.

You can use the same code many times with different arguments, to produce different results.

Example

Convert Fahrenheit to Celsius:

function toCelsius(fahrenheit) {

return (5/9) * (fahrenheit-32);

}

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = toCelsius(77);

Using the example above, toCelsius refers to the function object, and toCelsius() refers to the function result.

Example

Accessing a function without () will return the function definition:

function toCelsius(fahrenheit) {

return (5/9) * (fahrenheit-32);

}

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = toCelsius;

Functions can be used as variable values in formulas, assignments, and calculations.

Example

You can use:

var text = "The temperature is " + toCelsius(77) + " Celsius";

toCelsius(77) is a function with the value already.

Instead of:

var x = toCelsius(32);

var text = "The temperature is " + x + " Celsius";

Example

<p id="demo">Display the result here.</p>

<script>

function myFunction(name) {

return "Hello " + name;

}

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = myFunction("John")

</script>

Example

<h4>Define a function named "myFunction", and make it display "Hello World!" in the element.</h4>

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

function myFunction() {

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Hello World!";

}

myFunction()

</script>

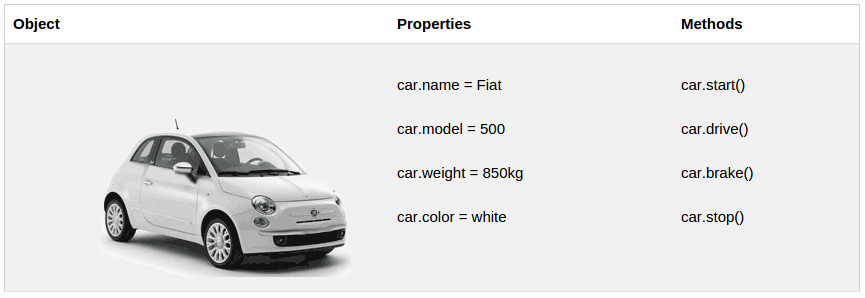

In real life, a car is an object.

A car has properties like weight and color, and methods like start and stop:

All cars have the same properties, but the property values differ from car to car.

All cars have the same methods, but the methods are performed at different times.

You have already learned that JavaScript variables are containers for data values.

This code assigns a simple value (Fiat) to a variable named car:

var car = "Fiat";

Objects are variables too. But objects can contain many values.

This code assigns many values (Fiat, 500, white) to a variable named car:

var car = {type:"Fiat", model:"500", color:"white"};

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var car = {type:"Fiat", model:"500", color:"white"};

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Type of Car: " + car.type;

</script>

The values are written as name:value pairs (name and value separated by a colon).

JavaScript objects are containers for named values.

The name:values pairs (in JavaScript objects) are called properties.

var person = {firstName:"John", lastName:"Doe", age:50, eyeColor:"blue"};

Methods are actions that can be performed on objects.

Methods are stored in properties as function definitions.

Property Property Value

firstName John lastName Doe age 50 eyeColor blue fullName function() {return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName;}

JavaScript objects are containers for named values (called properties) and methods.

You define (and create) a JavaScript object with an object literal:

Example

var person = {firstName:"John", lastName:"Doe", age:50, eyeColor:"blue"};

Example

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var person = {firstName:"John", lastName: "Doe", age: 50,

eyeColor: "blue"};

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = person.firstName + " is " + person.age + " years old";

</script>

Spaces and line breaks are not important. An object definition can span multiple lines:

Example

var person = {

firstName:"John",

lastName:"Doe",

age:50,

eyeColor:"blue"

};

You can access object properties in two ways:

objectName.propertyName

or

objectName["propertyName"]

Example1

person.lastName;

Example2

person["lastName"];

You access an object method with the following syntax:

objectName.methodName()

Example

name = person.fullName();

With the following code

var karyawan = {

namaDepan: "Dyo",

namaBelakang: "Bumi",

umur: 37,

id: 222,

// create method

namaLengkap: function() {

return this.namaDepan + " " + this.namaBelakang;

}

};

document.getElementById("coba").innerHTML = karyawan.namaLengkap();

If you access the fullName property, without (), it will return the function definition:

name = person.fullName;

Exercise:

Create an object called person with name = John, age = 50. Then, access the object to display "John is 50 years old".

Answwer

var person = {

name: "John",

age: 50

}

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = person.name + " is " + person.age + " years old";

When a JavaScript variable is declared with the keyword "new", the variable is created as an object:

var x = new String(); // Declares x as a String object

var y = new Number(); // Declares y as a Number object

var z = new Boolean(); // Declares z as a Boolean object

Avoid String, Number, and Boolean objects. They complicate your code and slow down execution speed.

Note You will learn more about objects later in this tutorial.

In JavaScript, objects and functions are also variables.

In JavaScript, scope is the set of variables, objects, and functions you have access to.

JavaScript has function scope: The scope changes inside functions.

Variables declared within a JavaScript function, become LOCAL to the function.

Local variables have local scope: They can only be accessed within the function.

Example

// code here can not use carName

function myFunction() {

var carName = "Volvo";

// code here can use carName

}

Other example

<p>The local variable carName cannot be accessed from code outside the function:</p>

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

myFunction(); // this is callback

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = /* this is

"The type of carName is " + typeof carName; how to print in js */

function myFunction() { /* this is

var carName = "Volvo"; the function */

}

</script>

Since local variables are only recognized inside their functions, variables with the same name can be used in different functions.

Local variables are created when a function starts, and deleted when the function is completed.

Example

var carName = " Volvo";

// code here can use carName

function myFunction() {

// code here can use carName

}

Example

<h1>It is call Global Variable</h1>

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var namaPegawai = "Brandon";

function myFunction() {

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = namaPegawai

}

myFunction();

</script>

If you assign a value to a variable that has not been declared, it will automatically become a GLOBAL variable.

This code example will declare a global variable carName, even if the value is assigned inside a function.

Not give var ... yet

Example

myFunction();

// code here can use carName

function myFunction() {

carName = "Volvo"; // not use var carName yet

}

Note Do NOT create global variables unless you intend to.

With JavaScript, the global scope is the complete JavaScript environment.

In HTML, the global scope is the window object. All global variables belong to the window object.

Example

var carName = "Volvo";

// code here can use window.carName

The lifetime of a JavaScript variable starts when it is declared.

Local variables are deleted when the function is completed.

Global variables are deleted when you close the page.

Function arguments (parameters) work as local variables inside functions.

HTML events are "things" that happen to HTML elements.

When JavaScript is used in HTML pages, JavaScript can "react" on these events.

An HTML event can be something the browser does, or something a user does.

Here are some examples of HTML events:

- An HTML web page has finished loading

- An HTML input field was changed

- An HTML button was clicked

Often, when events happen, you may want to do something.

JavaScript lets you execute code when events are detected.

HTML allows event handler attributes, with JavaScript code, to be added to HTML elements.

With single quotes:

<some-HTML-element some-event='some JavaScript'>

With double quotes:

<some-HTML-element some-event="some JavaScript">

In the following example, an onclick attribute (with code), is added to a button element:

Example

<button onclick='getElementById("demo").innerHTML=Date()'>The time is?</button>

<p id="demo"></p>

Example

In the example above, the JavaScript code changes the content of the element with id="demo".

In the next example, the code changes the content of its own element (using this.innerHTML):

Example

<button onclick="this.innerHTML=Date()">The time is?</button>

JavaScript code is often several lines long. It is more common to see event attributes calling functions:

Example

<button onclick="displayDate()">The time is?</button>

<script>

function displayDate() {

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = Date();

}

</script>

Here is a list of some common HTML events:

Event Description

onchange An HTML element has been changed

onclick The user clicks an HTML element

onmouseover The user moves the mouse over an HTML element

onmouseout The user moves the mouse away from an HTML element

onkeydown The user pushes a keyboard key

onload The browser has finished loading the page

The list is much longer: W3Schools JavaScript Reference HTML DOM Events.

Event handlers can be used to handle, and verify, user input, user actions, and browser actions:

Things that should be done every time a page loads Things that should be done when the page is closed Action that should be performed when a user clicks a button Content that should be verified when a user inputs data And more ...

Many different methods can be used to let JavaScript work with events:

HTML event attributes can execute JavaScript code directly HTML event attributes can call JavaScript functions You can assign your own event handler functions to HTML elements You can prevent events from being sent or being handled And more ...

You will learn a lot more about events and event handlers in the HTML DOM chapters.

JavaScript strings are used for storing and manipulating text.

A JavaScript string simply stores a series of characters like "John Doe".

A string can be any text inside quotes. You can use single or double quotes:

Example

var carname = "Volvo XC60";

var carname = 'Volvo XC60';

You can use quotes inside a string, as long as they don't match the quotes surrounding the string:

Example

var answer = "It's alright";

var answer = "He is called 'Johnny'";

var answer = 'He is called "Johnny"';

The length of a string is found in the built in property length:

Example

var txt = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ";

var sln = txt.length;

Detail

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var text = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ";

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Jumlah huruf " + text.length;

</script>

Because strings must be written within quotes, JavaScript will misunderstand this string:

var y = "We are the so-called "Vikings" from the north."

The string will be chopped to "We are the so-called ".

The solution to avoid this problem, is to use the \ escape character.

The backslash escape character turns special characters into string characters:

Example

var x = 'It\'s alright';

var y = "We are the so-called \"Vikings\" from the north."

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = x + "<br>" + y;

The escape character () can also be used to insert other special characters in a string.

This is the list of special characters that can be added to a text string with the backslash sign:

Code Outputs

\' single quote

\" double quote

\\ backslash

\n new line

\r carriage return

\t tab

\b backspace

\f form feed

For best readability, programmers often like to avoid code lines longer than 80 characters.

If a JavaScript statement does not fit on one line, the best place to break it is after an operator:

Example

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML =

"Hello Dolly.";

You can also break up a code line within a text string with a single backslash:

Example

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Hello \

Dolly!";

The \ method is not a ECMAScript (JavaScript) standard. Some browsers do not allow spaces behind the \ character.

The safest (but a little slower) way to break a long string is to use string addition:

Example

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = "Hello" +

"Dolly!";

You cannot break up a code line with a backslash:

Example

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = \

"Hello Dolly!";

Normally, JavaScript strings are primitive values, created from literals: var firstName = "John"

But strings can also be defined as objects with the keyword new: var firstName = new String("John")

Example

var x = "John";

var y = new String("John");

// typeof x will return string

// typeof y will return object

Example

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var x = "Brandon";

var y = new String("Bumi");

document.getElementById('demo').innerHTML =

"Type Data x = " + typeof x + "<br>" +

"Type Data y = " + typeof y;

</script>

Note: Don't create strings as objects. It slows down execution speed. The new keyword complicates the code. This can produce some unexpected results:

When using the == equality operator, equal strings looks equal:

Example

var x = "John";

var y = new String("John");

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = (x==y);

// (x == y) is true because x and y have equal values

When using the === equality operator, equal strings are not equal, because the === operator expects equality in both type and value.

Example

var x = "John";

var y = new String("John");

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = (x===y);

// (x === y) is false because x and y have different types (string and object)

Or even worse. Objects cannot be compared:

Example

var x = new String("John");

var y = new String("John");

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = (x==y);

// (x == y) is false because x and y are different objects

// (x == x) is true because both are the same object

Note: JavaScript objects cannot be compared.

String methods help you to work with strings.

Primitive values, like "John Doe", cannot have properties or methods (because they are not objects).

But with JavaScript, methods and properties are also available to primitive values, because JavaScript treats primitive values as objects when executing methods and properties.

The length property returns the length of a string:

Example

var txt = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ";

var sln = txt.length;

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = txt.length;

The indexOf() method returns the index of (the position of) the first occurrence of a specified text in a string:

Example

var str = "Please locate where 'locate' occurs!";

var pos = str.indexOf("locate");

The lastIndexOf() method returns the index of the last occurrence of a specified text in a string:

Example

var str = "Please locate where 'locate' occurs!";

var pos = str.lastIndexOf("locate");

Detail Code

<p id="p1">Please locate where 'locate' occurs!.</p>

<button onclick="myFunction()">Try it</button>

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

function myFunction() {

var str = document.getElementById("p1").innerHTML;

var pos = str.lastIndexOf("locate");

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = pos;

}

</script>

Both the indexOf(), and the lastIndexOf() methods return -1 if the text is not found.

Note JavaScript counts positions from zero. 0 is the first position in a string, 1 is the second, 2 is the third ...

Both methods accept a second parameter as the starting position for the search.

The search() method searches a string for a specified value and returns the position of the match:

Example

var str = "Please locate where 'locate' occurs!";

var pos = str.search("locate");

The two methods, indexOf() and search(), are equal.

They accept the same arguments (parameters), and they return the same value.

The two methods are equal, but the search() method can take much more powerful search values.

You will learn more about powerful search values in the chapter about regular expressions.

There are 3 methods for extracting a part of a string:

- slice(start, end)

- substring(start, end) The difference is that the second parameter specifies the length of the extracted part.

- substr(start, length)

slice() extracts a part of a string and returns the extracted part in a new string.

The method takes 2 parameters: the starting index (position), and the ending index (position).

This example slices out a portion of a string from position 7 to position 13:

Example

var str = "Apple, Banana, Kiwi";

var res = str.slice(7,13);

The result of res will be:

Banana

If a parameter is negative, the position is counted from the end of the string.

This example slices out a portion of a string from position -12 to position -6:

Example

var str = "Apple, Banana, Kiwi";

var res = str.slice(-12,-6);

The result of res will be:

Banana

If you omit (menghilangkan) the second parameter, the method will slice out the rest of the string:

Example

var res = str.slice(7);

var str = "Apple, Banana, Kiwi";

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = str.slice(7);

The result of res will be:

Banana, Kiwi

or, counting from the end:

Example

var res = str.slice(-12);

var str = "Apple, Banana, Kiwi";

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = str.slice(-12);

The result of res will be:

Banana, Kiwi

Note Negative positions do not work in Internet Explorer 8 and earlier.

substring() is similar to slice().

The difference is that substring() cannot accept negative indexes.

Example

var str = "Apple, Banana, Kiwi";

var res = str.substring(7,13);

The result of res will be:

Banana

If you omit the second parameter, substring() will slice out the rest of the string.

substr() is similar to slice().

The difference is that the second parameter specifies the length of the extracted part.

Example

var str = "Apple, Banana, Kiwi";

var res = str.substr(7,6);

The result of res will be:

Banana

If the first parameter is negative, the position counts from the end of the string.

The second parameter can not be negative, because it defines the length.

If you omit the second parameter, substr() will slice out the rest of the string.

The replace() method replaces a specified value with another value in a string:

Example

str = "Please visit Microsoft!";

var n = str.replace("Microsoft","W3Schools");

The replace() method can also take a regular expression as the search value.

By default, the replace() function replaces only the first match. To replace all matches, use a regular expression with a g flag (for global match):

Example

str = "Please visit Microsoft!";

var n = str.replace(/Microsoft/g,"W3Schools");

Note The replace() method does not change the string it is called on. It returns a new string.

A string is converted to upper case with toUpperCase():

Example

var text1 = "Hello World!"; // String

var text2 = text1.toUpperCase(); // text2 is text1 converted to upper

A string is converted to lower case with toLowerCase():

Example

var text1 = "Hello World!"; // String

var text2 = text1.toLowerCase(); // text2 is text1 converted to lower

concat() joins two or more strings:

Example

var text1 = "Hello";

var text2 = "World";

text3 = text1.concat(" ",text2);

The concat() method can be used instead of the plus operator. These two lines do the same:

Example

var text = "Hello" + " " + "World!";

var text = "Hello".concat(" ","World!");

All string methods return a new string. They don't modify the original string. Formally said: Strings are immutable: Strings cannot be changed, only replaced.

There are 2 safe methods for extracting string characters:

- charAt(position)

- charCodeAt(position)

The charAt() method returns the character at a specified index (position) in a string:

Example

var str = "HELLO WORLD";

str.charAt(0); // returns H

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = str.charAt(0);

The charCodeAt() method returns the unicode of the character at a specified index in a string:

Example

var str = "HELLO WORLD";

str.charCodeAt(0); // returns 72

You might have seen code like this, accessing a string as an array:

var str = "HELLO WORLD";

str[0]; // returns H

This is unsafe and unpredictable:

- It does not work in all browsers (not in IE5, IE6, IE7)

- It makes strings look like arrays (but they are not)

- str[0] = "H" does not give an error (but does not work)

If you want to read a string as an array, convert it to an array first.

A string can be converted to an array with the split() method:

Example

var txt = "a,b,c,d,e"; // String

txt.split(","); // Split on commas

txt.split(" "); // Split on spaces

txt.split("|"); // Split on pipe

If the separator is omitted, the returned array will contain the whole string in index [0].

If the separator is "", the returned array will be an array of single characters:

Example

var txt = "Hello"; // String

txt.split(""); // Split in characters

Detail code

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var str = "widyobumi";

var arr = str.split("");

var txt = "";

var i;

for (i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

txt += arr[i] + "<br>"

}

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = txt;

</script>

Catatan: Dalam for loop harus ada var txt = "", var i, i++, txt +=

For a complete reference, go to our Complete JavaScript String Reference.

The reference contains descriptions and examples of all string properties and methods.

JavaScript has only one type of number.

Numbers can be written with, or without, decimals.

Extra large or extra small numbers can be written with scientific (exponent) notation:

Example

var x = 123e5; // 12300000

var y = 123e-5; // 0.00123

Unlike many other programming languages, JavaScript does not define different types of numbers, like integers, short, long, floating-point etc.

JavaScript numbers are always stored as double precision floating point numbers, following the international IEEE 754 standard.

This format stores numbers in 64 bits, where the number (the fraction) is stored in bits 0 to 51, the exponent in bits 52 to 62, and the sign in bit 63:

Value (aka Fraction/Mantissa) Exponent Sign

52 bits (0 - 51) 11 bits (52 - 62) 1 bit (63)

Integers (numbers without a period or exponent notation) are considered accurate up to 15 digits.

Example

var x = 999999999999999; // x will be 999999999999999

var y = 9999999999999999; // y will be 10000000000000000

The maximum number of decimals is 17, but floating point arithmetic is not always 100% accurate:

Example

var x = 0.2 + 0.1; // x will be 0.30000000000000004

To solve the problem above, it helps to multiply and divide:

Example

var x = (0.2 * 10 + 0.1 * 10) / 10; // x will be 0.3

JavaScript interprets numeric constants as hexadecimal if they are preceded by 0x.

Example

var x = 0xFF; // x will be 255

Never write a number with a leading zero (like 07). Some JavaScript versions interpret numbers as octal if they are written with a leading zero.

By default, Javascript displays numbers as base 10 decimals.

But you can use the toString() method to output numbers as base 16 (hex), base 8 (octal), or base 2 (binary).

Example

var myNumber = 128;

myNumber.toString(16); // returns 80

myNumber.toString(8); // returns 200

myNumber.toString(2); // returns 10000000

Infinity (or -Infinity) is the value JavaScript will return if you calculate a number outside the largest possible number.

Example

var myNumber = 2;

while (myNumber != Infinity) { // Execute until Infinity

myNumber = myNumber * myNumber;

}

Division by 0 (zero) also generates Infinity:

Example

var x = 2 / 0; // x will be Infinity

var y = -2 / 0; // y will be -Infinity

Infinity is a number: typeOf Infinity returns number.

Example

typeof Infinity; // returns "number"

NaN is a JavaScript reserved word indicating that a value is not a number.

Trying to do arithmetic with a non-numeric string will result in NaN (Not a Number):

Example

var x = 100 / "Apple"; // x will be NaN (Not a Number)

However, if the string contains a numeric value , the result will be a number:

Example

var x = 100 / "10"; // x will be 10

You can use the global JavaScript function isNaN() to find out if a value is a number.

Example

var x = 100 / "Apple";

isNaN(x); // returns true because x is Not a Number

Watch out for NaN. If you use NaN in a mathematical operation, the result will also be NaN:

Example

var x = NaN;

var y = 5;

var z = x + y; // z will be NaN

Or the result might be a concatenation:

Example

var x = NaN;

var y = "5";

var z = x + y; // z will be NaN5

NaN is a number, and typeof NaN returns number:

Example

typeof NaN; // returns "number"

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = typeof NaN;

Result

number

Normally JavaScript numbers are primitive values created from literals: var x = 123

But numbers can also be defined as objects with the keyword new: var y = new Number(123)

Example

var x = 123;

var y = new Number(123);

// typeof x returns number

// typeof y returns object

Don not create Number objects. It slows down execution speed. The new keyword complicates the code. This can produce some unexpected results:

When using the == equality operator, equal numbers looks equal:

Example

var x = 500;

var y = new Number(500);

// (x == y) is true because x and y have equal values

When using the === equality operator, equal numbers are not equal, because the === operator expects equality in both type and value.

Example

var x = 500;

var y = new Number(500);

// (x === y) is false because x and y have different types

Or even worse. Objects cannot be compared:

Example

var x = new Number(500);

var y = new Number(500);

// (x == y) is false because objects cannot be compared

JavaScript objects cannot be compared.

Number methods help you work with numbers.

Primitive values (like 3.14 or 2014), cannot have properties and methods (because they are not objects).

But with JavaScript, methods and properties are also available to primitive values, because JavaScript treats primitive values as objects when executing methods and properties.

toString() returns a number as a string.

All number methods can be used on any type of numbers (literals, variables, or expressions):

Example

var x = 123;

x.toString(); // returns 123 from variable x

(123).toString(); // returns 123 from literal 123

(100 + 23).toString(); // returns 123 from expression 100 + 23

toExponential() returns a string, with a number rounded and written using exponential notation.

A parameter defines the number of characters behind the decimal point:

Example

var x = 9.656;

x.toExponential(2); // returns 9.66e+0

x.toExponential(4); // returns 9.6560e+0

x.toExponential(6); // returns 9.656000e+0

The parameter is optional. If you don't specify it, JavaScript will not round the number.

toFixed() returns a string, with the number written with a specified number of decimals:

Example

var x = 9.656;

x.toFixed(0); // returns 10

x.toFixed(2); // returns 9.66

x.toFixed(4); // returns 9.6560

x.toFixed(6); // returns 9.656000

toFixed(2) is perfect for working with money.

toPrecision() returns a string, with a number written with a specified length:

Example

var x = 9.656;

x.toPrecision(); // returns 9.656

x.toPrecision(2); // returns 9.7

x.toPrecision(4); // returns 9.656

x.toPrecision(6); // returns 9.65600

valueOf() returns a number as a number.

Example

var x = 123;

x.valueOf(); // returns 123 from variable x

(123).valueOf(); // returns 123 from literal 123

(100 + 23).valueOf(); // returns 123 from expression 100 + 23

In JavaScript, a number can be a primitive value (typeof = number) or an object (typeof = object).

The valueOf() method is used internally in JavaScript to convert Number objects to primitive values.

There is no reason to use it in your code.

A JavaScript data types have a valueOf() and a toString() method.

There are 3 JavaScript methods that can be used to convert variables to numbers:

- The Number() method

- The parseInt() method

- The parseFloat() method

These methods are not number methods, but global JavaScript methods.

JavaScript global methods can be used on all JavaScript data types.

These are the most relevant methods, when working with numbers:

Method Description

Number() Returns a number, converted from its argument.

parseFloat() Parses its argument and returns a floating point number

parseInt() Parses its argument and returns an integer

Number() can be used to convert JavaScript variables to numbers:

Example

x = true;

Number(x); // returns 1

x = false;

Number(x); // returns 0

x = new Date();

Number(x); // returns 1404568027739

x = "10"

Number(x); // returns 10

x = "10 20"

Number(x); // returns NaN

parseInt() parses a string and returns a whole number. Spaces are allowed. Only the first number is returned:

Example

parseInt("10"); // returns 10

parseInt("10.33"); // returns 10

parseInt("10 20 30"); // returns 10

parseInt("10 years"); // returns 10

parseInt("years 10"); // returns NaN

If the number cannot be converted, NaN (Not a Number) is returned.

parseFloat() parses a string and returns a number. Spaces are allowed. Only the first number is returned:

Example

parseFloat("10"); // returns 10

parseFloat("10.33"); // returns 10.33

parseFloat("10 20 30"); // returns 10

parseFloat("10 years"); // returns 10

parseFloat("years 10"); // returns NaN

If the number cannot be converted, NaN (Not a Number) is returned.

Property Description

MAX_VALUE Returns the largest number possible in JavaScript

MIN_VALUE Returns the smallest number possible in JavaScript

NEGATIVE_INFINITY Represents negative infinity (returned on overflow)

NaN Represents a "Not-a-Number" value

POSITIVE_INFINITY Represents infinity (returned on overflow)

Example

var x = Number.MAX_VALUE;

Number properties belongs to the JavaScript's number object wrapper called Number.

These properties can only be accessed as Number.MAX_VALUE.

Using myNumber.MAX_VALUE, where myNumber is a variable, expression, or value, will return undefined:

Example

var x = 6;

var y = x.MAX_VALUE; // y becomes undefined

Complete JavaScript Number Reference

For a complete reference, go to our Complete JavaScript Number Reference.

The reference contains descriptions and examples of all Number properties and methods.

The Math object allows you to perform mathematical tasks on numbers.

The Math object allows you to perform mathematical tasks.

The Math object includes several mathematical methods.

One common use of the Math object is to create a random number:

Example

Math.random(); // returns a random number

Math.random() always returns a number lower than 1.

Math has no constructor. No methods have to create a Math object first.

Math.min() and Math.max() can be used to find the lowest or highest value in a list of arguments:

Example

Math.min(0, 150, 30, 20, -8, -200); // returns -200

Example

Math.max(0, 150, 30, 20, -8, -200); // returns 150

Math.round() rounds a number to the nearest integer:

Example

Math.round(4.7); // returns 5

Math.round(4.4); // returns 4

Math.ceil() rounds a number up to the nearest integer:

Example

Math.ceil(4.4); // returns 5

Math.floor() rounds a number down to the nearest integer:

Example

Math.floor(4.7); // returns 4

Math.floor() and Math.random() can be used together to return a random number between 0 and 10:

Example

Math.floor(Math.random() * 11); // returns a random number between 0 and 10

JavaScript provides 8 mathematical constants that can be accessed with the Math object:

Example

Math.E // returns Euler's number

Math.PI // returns PI

Math.SQRT2 // returns the square root of 2

Math.SQRT1_2 // returns the square root of 1/2

Math.LN2 // returns the natural logarithm of 2

Math.LN10 // returns the natural logarithm of 10

Math.LOG2E // returns base 2 logarithm of E

Math.LOG10E // returns base 10 logarithm of E

Method Description

abs(x) Returns the absolute value of x

acos(x) Returns the arccosine of x, in radians

asin(x) Returns the arcsine of x, in radians

atan(x) Returns the arctangent of x as a numeric value between -PI/2 and PI/2 radians

atan2(y,x) Returns the arctangent of the quotient of its arguments

ceil(x) Returns x, rounded upwards to the nearest integer

cos(x) Returns the cosine of x (x is in radians)

exp(x) Returns the value of Ex

floor(x) Returns x, rounded downwards to the nearest integer

log(x) Returns the natural logarithm (base E) of x

max(x,y,z,...,n) Returns the number with the highest value

min(x,y,z,...,n) Returns the number with the lowest value

pow(x,y) Returns the value of x to the power of y

random() Returns a random number between 0 and 1

round(x) Rounds x to the nearest integer

sin(x) Returns the sine of x (x is in radians)

sqrt(x) Returns the square root of x

tan(x) Returns the tangent of an angle

For a complete reference, go to our complete Math object reference.

The reference contains descriptions and examples of all Math properties and methods.

The Date object lets you work with dates (years, months, days, hours, minutes, seconds, and milliseconds)

A JavaScript date can be written as a string:

Sun Jul 10 2016 07:50:46 GMT+0700 (WIB)

or as a number:

1468111846839

Dates written as numbers, specifies the number of milliseconds since January 1, 1970, 00:00:00.

In this tutorial we use a script to display dates inside a

element with id="demo":

Example

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = Date();

</script>

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var d = Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

The script above says: assign the value of Date() to the content (innerHTML) of the element with id="demo".

You will learn how to display a date, in a more readable format, at the bottom of this page.

The Date object lets us work with dates.

A date consists of a year, a month, a day, an hour, a minute, a second, and milliseconds.

Date objects are created with the new Date() constructor.

There are 4 ways of initiating a date:

new Date()

new Date(milliseconds)

new Date(dateString)

new Date(year, month, day, hours, minutes, seconds, milliseconds)

Using new Date(), creates a new date object with the current date and time:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

Using new Date(date string), creates a new date object from the specified date and time:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date("October 13, 2014 11:13:00");

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

Valid date strings (date formats) are described in the next chapter.

Using new Date(number), creates a new date object as zero time plus the number.

Zero time is 01 January 1970 00:00:00 UTC. The number is specified in milliseconds:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date(86400000);

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

JavaScript dates are calculated in milliseconds from 01 January, 1970 00:00:00 Universal Time (UTC). One day contains 86,400,000 millisecond.

Using new Date(7 numbers), creates a new date object with the specified date and time:

The 7 numbers specify the year, month, day, hour, minute, second, and millisecond, in that order:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date(99,5,24,11,33,30,0);

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

Variants of the example above let us omit any of the last 4 parameters:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date(99,5,24);

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

JavaScript counts months from 0 to 11. January is 0. December is 11.

When a Date object is created, a number of methods allow you to operate on it.

Date methods allow you to get and set the year, month, day, hour, minute, second, and millisecond of objects, using either local time or UTC (universal, or GMT) time.

Date methods are covered in a later chapter.

When you display a date object in HTML, it is automatically converted to a string, with the toString() method.

Example

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

Is the same as:

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d.toString();

</script>

The toUTCString() method converts a date to a UTC string (a date display standard).

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d.toUTCString();

</script>

The toDateString() method converts a date to a more readable format:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d.toDateString();

</script>

Date objects are static. The computer time is ticking, but date objects, once created, are not.

When setting a date, without specifying the time zone, JavaScript will use the browser's time zone.

When getting a date, without specifying the time zone, the result is converted to the browser's time zone.

In other words: If a date/time is created in GMT (Greenwich Mean Time), the date/time will be converted to CDT (Central US Daylight Time) if a user browses from central US.

Read more about time zones in the next chapters.

JavaScript Date Input

There are generally 4 types of JavaScript date input formats:

Type Example

ISO Date "2015-03-25" (The International Standard)

Short Date "03/25/2015" or "2015/03/25"

Long Date "Mar 25 2015" or "25 Mar 2015"

Full Date "Wednesday March 25 2015"

Independent of input format, JavaScript will (by default) output dates in full text string format:

Wed Mar 25 2015 07:00:00 GMT+0700 (WIB)

ISO 8601 is the international standard for the representation of dates and times.

The ISO 8601 syntax (YYYY-MM-DD) is also the preferred JavaScript date format:

var d = new Date("2015-03-25");

The computed date will be relative to your time zone. Depending on your time zone, the result above will vary between March 24 and March 25.

It can be written without specifying the day (YYYY-MM):

Example (Year and month)

var d = new Date("2015-03");

Time zones will vary the result above between February 28 and March 01.

It can be written without month and day (YYYY):

Example (Only year)

var d = new Date("2015");

Time zones will vary the result above between December 31 2014 and January 01 2015.

It can be written with added hours, minutes, and seconds (YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS):

Example (Complete date plus hours, minutes, and seconds)

var d = new Date("2015-03-25T12:00:00");

The T in the date string, between the date and time, indicates UTC time.

UTC (Universal Time Coordinated) is the same as GMT (Greenwich Mean Time).

JavaScript Short Dates. Short dates are most often written with an "MM/DD/YYYY" syntax like this:

Example

var d = new Date("03/25/2015");

Read more here: http://www.w3schools.com/js/js_date_formats.asp

Date methods let you get and set date values (years, months, days, hours, minutes, seconds, milliseconds)

Get methods are used for getting a part of a date. Here are the most common (alphabetically):

Method Description

getDate() Get the day as a number (1-31)

getDay() Get the weekday as a number (0-6)

getFullYear() Get the four digit year (yyyy)

getHours() Get the hour (0-23)

getMilliseconds() Get the milliseconds (0-999)

getMinutes() Get the minutes (0-59)

getMonth() Get the month (0-11)

getSeconds() Get the seconds (0-59)

getTime() Get the time (milliseconds since January 1, 1970)

getTime() returns the number of milliseconds since January 1, 1970:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d.getTime();

</script>

getFullYear() returns the year of a date as a four digit number:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d.getFullYear();

</script>

getDay() returns the weekday as a number (0-6):

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d.getDay();

</script>

In JavaScript, the first day of the week (0) means "Sunday", even if some countries in the world consider the first day of the week to be "Monday"

You can use an array of names, and getDay() to return the weekday as a name:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

var days = ["Sunday","Monday","Tuesday","Wednesday","Thursday","Friday","Saturday"];

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = days[d.getDay()];

</script>

Set methods are used for setting a part of a date. Here are the most common (alphabetically):

Method Description

setDate() Set the day as a number (1-31)

setFullYear() Set the year (optionally month and day)

setHours() Set the hour (0-23)

setMilliseconds() Set the milliseconds (0-999)

setMinutes() Set the minutes (0-59)

setMonth() Set the month (0-11)

setSeconds() Set the seconds (0-59)

setTime() Set the time (milliseconds since January 1, 1970)

setFullYear() sets a date object to a specific date. In this example, to January 14, 2020:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

d.setFullYear(2020, 0, 14);

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

setDate() sets the day of the month (1-31):

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

d.setDate(20);

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

The setDate() method can also be used to add days to a date:

Example

<script>

var d = new Date();

d.setDate(d.getDate() + 50);

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

If adding days, shifts the month or year, the changes are handled automatically by the Date object.

If you have a valid date string, you can use the Date.parse() method to convert it to milliseconds.

Date.parse() returns the number of milliseconds between the date and January 1, 1970:

Example

<script>

var msec = Date.parse("March 21, 2012");

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = msec;

</script>

You can then use the number of milliseconds to convert it to a date object:

Example

<script>

var msec = Date.parse("March 21, 2012");

var d = new Date(msec);

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = d;

</script>

Dates can easily be compared.

The following example compares today's date with January 14, 2100:

Example

var today, someday, text;

today = new Date();

someday = new Date();

someday.setFullYear(2100, 0, 14);

if (someday > today) {

text = "Today is before January 14, 2100.";

} else {

text = "Today is after January 14, 2100.";

}

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = text;

JavaScript counts months from 0 to 11. January is 0. December is 11.

UTC date methods are used for working UTC dates (Univeral Time Zone dates):

Method Description

getUTCDate() Same as getDate(), but returns the UTC date

getUTCDay() Same as getDay(), but returns the UTC day

getUTCFullYear() Same as getFullYear(), but returns the UTC year

getUTCHours() Same as getHours(), but returns the UTC hour

getUTCMilliseconds() Same as getMilliseconds(), but returns the UTC milliseconds

getUTCMinutes() Same as getMinutes(), but returns the UTC minutes

getUTCMonth() Same as getMonth(), but returns the UTC month

getUTCSeconds() Same as getSeconds(), but returns the UTC seconds

Complete JavaScript Date Reference

For a complete reference, go to our Complete JavaScript Date Reference.

The reference contains descriptions and examples of all Date properties and methods.

JavaScript arrays are used to store multiple values in a single variable.

Example

var cars = ["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"];

An array is a special variable, which can hold more than one value at a time.

If you have a list of items (a list of car names, for example), storing the cars in single variables could look like this:

var car1 = "Saab";

var car2 = "Volvo";

var car3 = "BMW";

However, what if you want to loop through the cars and find a specific one? And what if you had not 3 cars, but 300?

The solution is an array!

An array can hold many values under a single name, and you can access the values by referring to an index number.

Using an array literal is the easiest way to create a JavaScript Array.

Syntax:

var array-name = [item1, item2, ...];

Example

var cars = ["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"];

Spaces and line breaks are not important. A declaration can span multiple lines:

Example

var cars = [

"Saab",

"Volvo",

"BMW"

];

Never put a comma after the last element (like "BMW",). The effect is inconsistent across browsers.

The following example also creates an Array, and assigns values to it:

Example

var cars = new Array("Saab", "Volvo", "BMW");

Example

<p id="demo"></p>

<script>

var pets = new Array("Cat","Dog","Bird");

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = pets;

</script>

The three examples above do exactly the same. There is no need to use new Array(). For simplicity, readability and execution speed, use the first one (the array literal method).

You refer to an array element by referring to the index number.

This statement accesses the value of the first element in cars:

var name = cars[0];

This statement modifies the first element in cars:

cars[0] = "Opel";

Example

var cars = ["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"];

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = cars[0];

The answer is:

Saab

[0] is the first element in an array. [1] is the second. Array indexes start with 0.

With JavaScript, the full array can be accessed by referring to the array name:

Example

var cars = ["Saab", "Volvo", "BMW"];

document.getElementById("demo").innerHTML = cars;